Decades ago, on a project in Finland I encountered clearing and settlement for the first time. However, after a while it dawned on me that project members, including the client had different views on the meaning of clearing and settlement, complicated by language – I had to start meetings by double checking we were discussing “suoritus” or “toimitus”, otherwise confusion reigned.

To this day, I am surprised by how many in payments and banking have only a hazy notion of clearing and settlement and the difference between them.

They are fundamental to payment systems, as is the role of central bank reserves in the settlement of payments.

Clearing and Settlement

I expect many readers do know the difference between clearing and settlement in payments and can skip this section, otherwise read on.

Clearing is the process of making good the result of a payment in the sending and receiving accounts.

To illustrate, when a payment leaves account A in Bank A and is credited to the recipient’s account B in Bank B, the payment is cleared in both accounts.

However, Bank A has taken the funds from account A and credited its own internal account e.g. a treasury account, while Bank B has credited the recipient’s account B from its own treasury account. This leaves Bank A owing Bank B.

Settlement is the process where banks settle the funds they owe each other. It is done on a ledger where both banks have accounts. Banks could have accounts on each other’s ledger, as happens with correspondent banking and cross-border payments; but typically for domestic payments, settlement occurs between accounts on the central bank ledger. In the example, Bank A uses its settlement account at the central bank to credit Bank B’s settlement account, executed typically through the central bank’s RTGS (real-time gross settlement system).

The timing and operation of clearing and settlement processes vary by clearing system. For example, in the UK, with FPS, clearing between bank accounts is instant (in most cases) and settlement follows later, when banks net-off the flows with each other and settle three times per business day. Some real-time payment systems such as NPP in Australia clear and settle for every transaction at the same time. With batch systems, such as the UK’s Bacs, the banks settle with each other first at the central bank then apply the clearings to their customer accounts the following day. High value systems such as CHAPS in the UK (T2 in Europe, Fedwire in the USA etc) may stagger the clearing where the sending bank takes the funds from the customer’s account and settles with the receiving bank specifically for that payment sometime later in the day. The receiving bank credits its customer soon after (the “real-time” in RTGS applies only to the settlement rather than to the end-to-end clearing).

When a bank’s customer pays a customer of the same bank, the transaction is known as “on-us” and settles on the bank’s own ledger without interbank clearing, or settlement at the central bank.

Central Bank Reserves

The funds held by banks to settle with each other at a central bank are known as reserves. Reserves are one of three types of money used in banking – the other two being commercial bank deposits and banknotes/coins. However, whereas deposits and banknotes (sometimes, as a pair, called broad money) are for use in the general economy, reserves (sometimes called narrow money) may be held only by financial institutions with accounts at the central bank. Reserves may be transacted only between these FIs, typically through a RTGS.

Reserves fluctuate with daily operations, but to get a feel for their size, some examples are: Lloyds (27m customers - UK) with reserves at the Bank of England (BoE) of around £62bn, Bank of America (69m customers - USA) with $332bn at the Federal Reserve and Abn Amro (5m customers - Netherlands) with €44bn at the ECB, according to their latest annual reports.

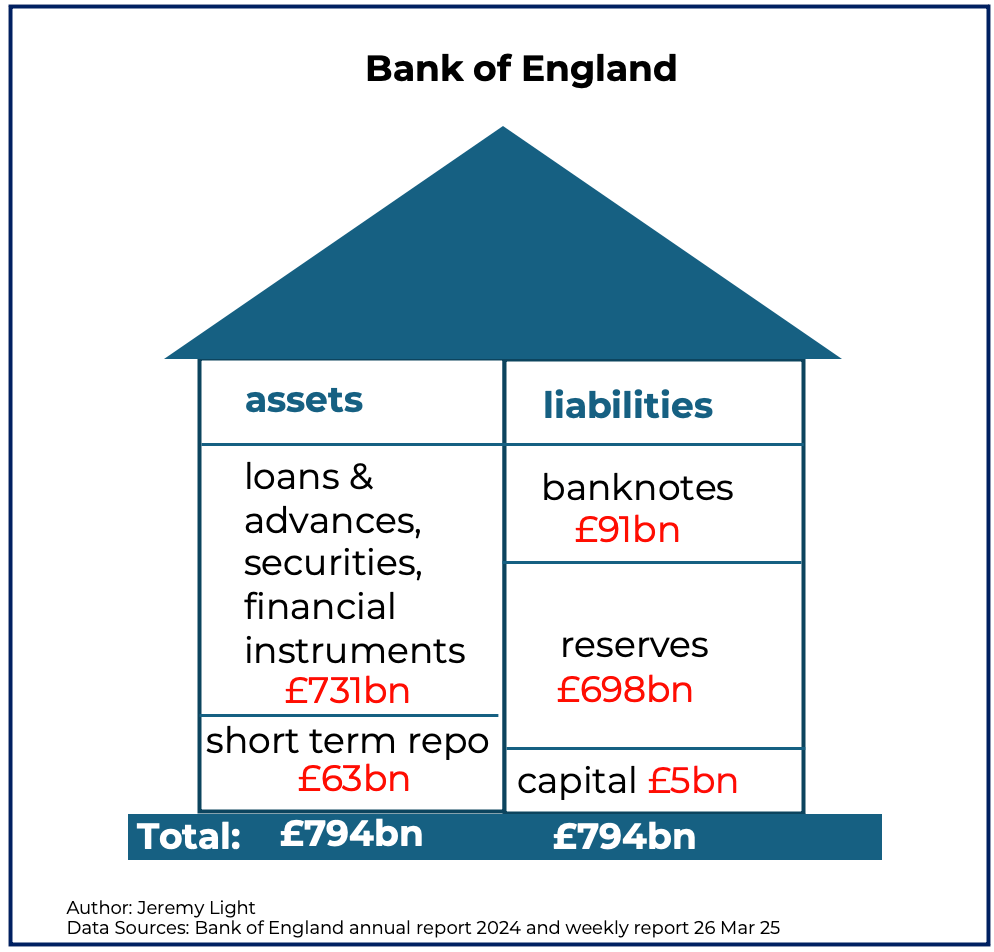

For a central bank example, Figure 1 shows a simplified balance sheet1 for the BoE. Aside from capital, the BoE’s liabilities are the banknotes circulating in the economy and the reserves it holds for all commercial banks. These are matched by assets such as government securities, loans and other financial instruments.

During periods of quantitative easing (QE), the BoE purchased large quantities of government debt into its Assets Purchase Facility (APF - mainly through commercial banks, but in effect purchasing direct from the government) causing its assets to go up and its reserves to rise in unison. For example, QE raised the BoE’s total assets from £590bn in 2020 to £1,130bn in 20222 and its reserves from £473bn at the start of 2020 to a peak of £979bn in January 2022.

Figure 1 – Bank of England simplified balance sheet as of 26 March 2025

Money Creation and Payments

All deposits held at a commercial bank are created as loans. When a bank, Bank A, issues a loan, it creates the money by crediting the borrower’s account with a deposit. The deposit is recorded as a liability on its books and the loan as a matching asset. However, it is likely the borrower will use the money to pay someone at another bank, Bank B, requiring Bank A to settle with Bank B, which it does typically in central bank reserves. Bank A has no control over how the money it creates circulates between banks or between its own customers. Always, it must have sufficient reserves to meet its settlement obligations with other banks, thus its lending is limited by the level of its reserves at the central bank3.

Banks increase their reserves by attracting deposits from customers at other banks, through physical cash deposited by their own customers, or by borrowing reserves from other banks or from the central bank itself.

To illustrate with real numbers, Figure 1 shows the BoE’s total reserves currently at around £698bn. In February this year, the total payments between banks processed for the month was £7.8trn4 or £392bn per business day. Most of this was processed through the CHAPS high value payment system at £352bn, the remaining £40bn split between FPS at £18bn per day and Bacs at £22bn (plus £0.5bn per day for cheques).

Each bank has their own payment flows and reserve requirements, so it is impossible to tell from this data what reserves in aggregate are needed for the smooth running and settlement of UK payments each day. However, the total gross interbank payment daily flow of £392bn is the upper limit (on average for February) of the reserves needed, which is well below the total reserves of £698bn.

UK banks are awash with liquidity and have been since QE ramped up in 2020 in response to the lockdowns. The BoE ended its QE purchases in late 2021 and since September 2022 has been selling bonds in the APF, in a process called quantitative tightening (QT), which has the effect of reducing reserves.

Short Term Repos

Commercial banks may borrow reserves overnight from the BoE in exchange for collateral (government bonds) by paying the Bank Rate5 + 0.25%, on a weekly basis by paying Bank Rate through the Short Term Repo (STR)6 facility and for six months through the ILTR (indexed long-term repo) by bidding for them at a rate set in an auction with the BoE.

When aggregate reserves reduce as QT proceeds, banks have more work to do to manage their own reserves to meet their daily payment obligations (and regulatory minima) using these BoE facilities. With such a wide cushion between the total reserves and those needed for settling payments, you would think it would be some time before QT required more active reserves management.

However, although the STR was used little when introduced in 2022, weekly borrowing started to take off later in 2023, reaching £63bn at the end of last month, almost 10% of all reserves – see Figure 2 (and Figure 1 where I have separated out the BoE’s assets held through the STR). So, even though reserves in aggregate exceed the daily value of interbank payments by a wide margin, some banks still need to use the STR extensively to meet their reserve requirements.

Figure 2 – Short Term Repo borrowing for Bank of England reserves7

The STR is in effect a short-term QE mechanism and its growing use could be interpreted mistakenly as a sign of stress in the financial system8. However, the BoE expected this to materialise9. It planned for a reserves scarcity environment to result from QT and for banks to transition to a repo-led, demand-driven framework using the ILTR and the STR.

It does suggest that payment flows between banks are lopsided, with some seeing periods of net outflows, requiring more reserves and others seeing net inflows, requiring fewer reserves.

At the end of January 2018, total reserves were £472bn, far lower than today, but the average daily interbank flows at £357bn were similar to February 2025. This shows significantly more reserves are needed today to settle interbank payments than before. This may be due to changes in payment flows between banks, but it suggests that settlement has become less efficient. Prior to 2022 when the STR was introduced, banks with excess reserves used to lend them to banks who needed them. Today, the STR disincentivises interbank lending – it is often cheaper for banks to use the STR to boost their reserves than to borrow from other banks with excess reserves, leading to an overall increase in reserves.

Conclusion

This article covers the basics of clearing, settlement, central bank reserves and the operations around them. For those interested in the subject, the Bank of England publishes useful papers, some are timeless, published years ago10 but are still insightful and relevant.

The examples given here are for the BoE, but other central banks use reserves in a similar way and have similar liquidity management tools for them e.g. the Federal Reserve in the USA has the Overnight Reverse Repo (ON RRP) facility, the Standing Repo Facility (SRF) for emergency liquidity and daily repo auctions.

From a payments perspective, the key message is that all domestic interbank payments settle ultimately through a central bank using central bank reserves.

However, with CBDCs, stablecoins, tokenised deposits and other new forms of digital money on the horizon, the role of central banks in payments will change. CBDCs are an attempt by central banks to remain relevant in payments but they would change the dynamics of money creation and lending in the economy, ultimately disrupting the use of reserves and the way banking systems operate.

Stablecoins and tokenised deposits require no central bank settlement, payments are settled on the blockchain where they are issued, which is why the BoE, for example, is wary of stablecoins, especially for wholesale use11. If stablecoins or tokenised deposits get product-market fit for retail and corporate use, the creation and lending of money should be as before, but the way payments and reserves operate will change12.

Thus, it is more important than ever to understand the nuts and bolts of payments including the role of central banks, central bank reserves, clearing and settlement. By getting to grips with reserves and knowing your “suoritus” from your “toimitus”, you are equipped to make sense of the innovations to come.

Erratum:

Last week’s post had a diagram with incorrect estimates for on-us wallet transactions in China. These are corrected on the diagram below.

Sterling only, no currencies (~£14bn), ignores detail of the two BoE reporting entities (Banking Department and Issuing Department), equity capital: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/annual-report/2024/boe-2024.pdf#page=8 – data as of 26 Mar 25 - RPWB55A (banknotes), RPWB56B (reserves), RPWB67A (short term repo) https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/weekly-report/balance-sheet-and-weekly-report

Bank of England Annual Reports 2020: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/annual-report/2020/boe-2020.pdf#page=7 and 2022: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/annual-report/2022/boe-2022.pdf#page=8

-commercial banks must meet specific regulatory requirements such as for liquidity cover ratios (LCR), net stable funding ratios (NSFR), capital adequacy ratios (CAR) and common equity tier 1 ratios (CET1)

- commercial banks can lend more than their reserves. Commercial bank reserves = total loans issued – deposits held – loans issued paid to accounts at other banks

Bank Rate is the rate of interest on central bank reserves the BoE sets and pays to commercial banks

-“repo” is short for “repurchase agreement where one party sells a security to another and agrees to repurchase it later from the buyer at an agreed price, usually a lower price. It is a form of borrowing where the interest cost is the difference between the selling and repurchase price.

- Bank of England liquidity tools https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/markets/bank-of-england-market-operations-guide/our-tools

a sign of stress in reserves is usually a spike in interbank lending rates, rather than the amounts lent. Heightened interbank rates imply banks are unwilling to lend to each other due to risk, as happened at the start of the GFC when interbank LIBOR rates rose sharply in early August 2007. The STR reduces much of the need for interbank lending in the UK and is done at the Bank Rate set by the BoE rather than at a market rate. Any UK interbank lending is done at the SONIA reported rate. A spike in this rate may be a sign of stress, rather than the level of STR usage, provided the collateral used is high quality.

Bank of England Market Operations Guide: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/markets/bank-of-england-market-operations-guide/our-objectives

Understanding the Central Bank Balance Sheet: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/ccbs/resources/understanding-the-central-bank-balance-sheet.pdf

Monetary Operations: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/ccbs/resources/monetary-operations.pdf

Bank of England discussion paper, section 4.1.4 https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/paper/2024/the-boes-approach-to-innovation-in-money-and-payments.pdf

My view is that stablecoins will get traction for regular cross-border payments in USD, but domestic use is unlikely to happen soon (except perhaps in the USA). Tokenised bank deposits may get traction for corporate and internal use, as demonstrated by JPM Coin/Kinexys, but are also a long way off, if at all, for regular retail and business use.